I felt pride and anticipation as I pulled Rhonda the Honda up next to the eucalyptus trees running through the canyon along the suburbs. It took effort to get here. The morning had included an hour of pushing back against depression from the safety of my bed, then leading a mentoring meeting where my full presence was required. And of course there were the typical in's and out's of caring for a toddler. But I had decided the exercise and a touch of nature were a worthy exchange for pulling on my hiking shoes, despite the cloud of fatigue that had been shrouding my body from chronic illness.

The forest was calling and I would go! As soon as I was challenged to "take a picture in nature and share it with a quote from the book" I knew this was where I wanted to take it. But my hike didn't go as anticipated.

Capturing Nature

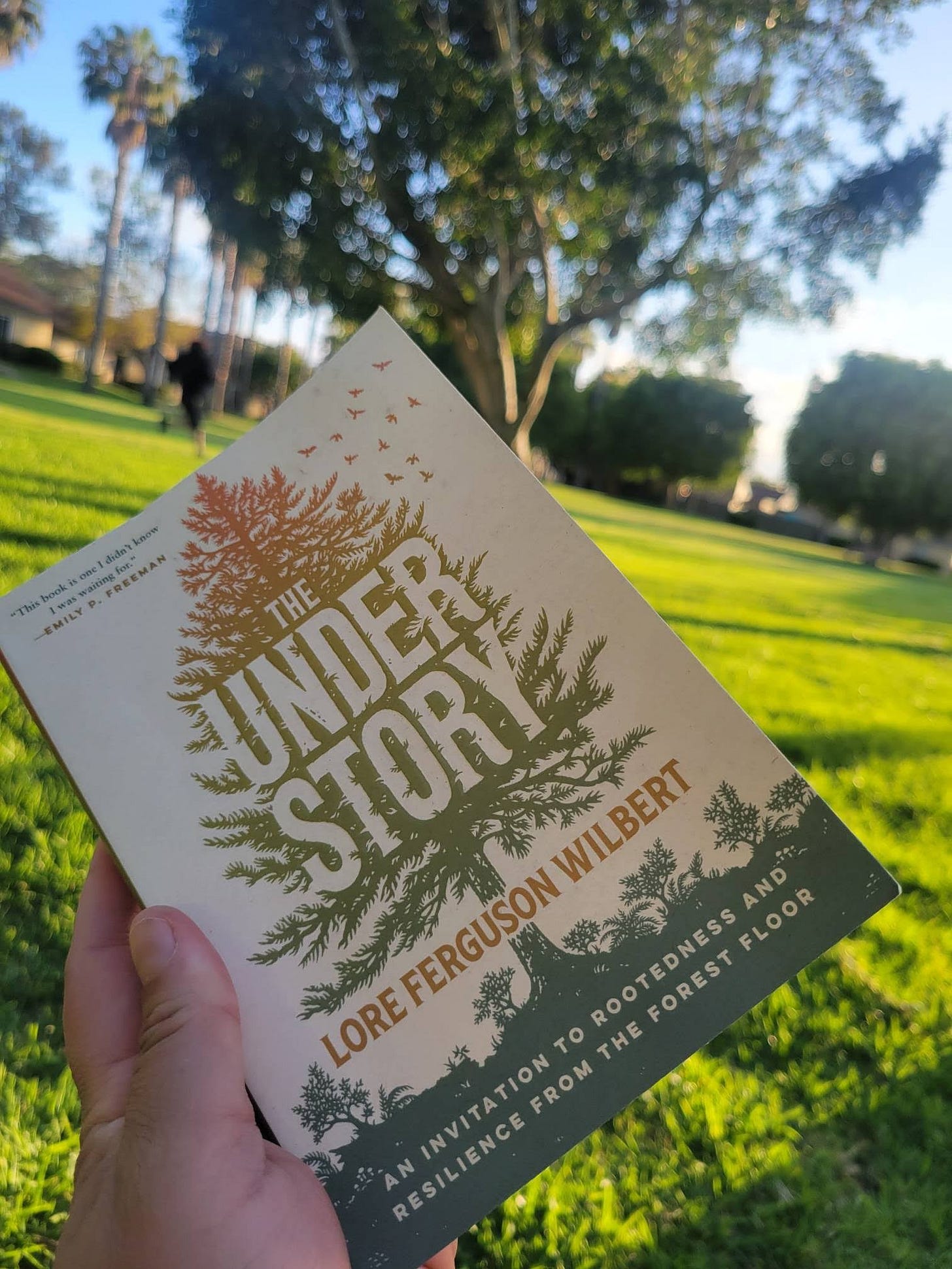

If I am honest, I spontaneously joined

launch team. She is a new-to-me writer. I found her earlier this year when I stumbled on an article where she shared about the process of choosing a cover for The Understory: An invitation to rootedness and resilience from the forest floor.I began to wonder how a designer can start with the vastness of nature, or in this case, a forest, and then create, create, and create . . . only for a publication team to narrow it down to one image. Humankind has been trying to capture creation since our inception. But it is only when something is determined as a worthy mirror nature that it is named art.

I have a wall of paintings in my home, mostly scenes of the ocean. My great grandma, grandma, and mom were/are all master artists. Each of them have their own rendition of the sea on my wall, whether through oil, watercolor, or acrylic. I added my own to this collection, and so have some of my own children. Five generations of art and not one of our pieces looks like another. A combination of all our art would never even get close to representing the Pacific, let alone nature in general.

As writing is its own art form, I was intrigued by how Lore Fergeson Wilbert would capture nature. Would she be able to do it justice? And how would she use the forest floor to invite us into a story of rootedness and resilience?

Sustainable Farm and Soil

I convinced my ten-year old to watch a short documentary with me about a sustainable farm in Southern California, The Biggest Little Farm: The Return. I had already watched it a couple months ago—mostly to try to distract my toddler long enough to write with farm animals.

He wasn't mesmerized by the animals. I, however, was mesmerized by the farm. Within a decade—less actually—a couple who had no experience with farming guided an exploited and dead lemon tree grove into a vibrant and diverse ecosystem. My ten-year old was just as fascinated by the rebirth of the land as I was. Twenty minutes later, my husband came and sat down next to me and we watched it again.

Soil is a living thing. Unless its biome includes an extensive and varied food chain, it cannot flourish. It might even need some cultivation, like Eden. The essential ingredient is nutrient-rich soil—formed by minuscule organisms busily decomposing the decaying life that then provides for the ground, just as the ground provides for us.

When I read Lore's chapter on soil, it alluded to aspects of soil that were also in the sustainable farm documentary. I realized I’ve never really appreciated the difference between dirt and soil, let alone the ripples of the ground’s impact. Last month I began Kristin Hannah's The Four Winds, a historical fiction about the Dust Bowl in Texas. It was dirt that forced the main character to migrate to California. How many of my fellow Californians are here because their parents or grandparents fled the Dust Bowl?

The loquat tree

I have a loquat tree that has been an enigma to me for years. Not only have I kept it alive—which feels like a miracle in and of itself—but it looks like it is flourishing. Yet it won't produce fruit.

During the last two painful years, I began wondering if this tree was a prophetic symbol of my own life. I too have been masterfully pruned. I keep growing. And I can present well. But despite all those things, am I actually producing fruit? Has all of this pain been for nothing, having no value? I thought, if I could just get the loquat to produce, then maybe I would, too.

I finally spoke with a gardener about it (not my life, but the tree, whose fruit production I was determined to get rolling). He asked me what the PH level of the soil was and what types of fertilizers I’d been using.

"It's pretty simple. It just needs the right nutrients. Otherwise it might look great, but it will never produce."

I couldn't help but remember Jesus cursing the fig tree, an object lesson if there ever was one.1 I wonder now it that was more of a statement about the soil the tree was planted in than the tree's lack of production.

Soil is a miracle. And as I read Lore's metaphors of the soil I found myself crying. She shared about the mud, which we walk through to stand upright when suffering and the will of God meet. She shared about the painful call-outs of power abuse, which change the landscape of relationships. They are earthquakes severing the earth.

I knew the ground of them both.

Within twenty-four hours of reading Lore’s chapter and watching the farm documentary again, I also watched an episode of Chosen where, incidentally, the women made miracle soil to regenerate an olive grove. Then, I read about the elements of soil and how it is formed in a fantasy novel.

Jesus hasn’t been tramping around my backyard to tell my loquat tree to wither, nor is he dumping manure in the dirt around it. But he is undoubtedly whispering through the ruffling tree’s leaves something very important about soil.

“…You cannot be fruitful unless you remain in me…Remain in my love.” (John 15:4b,9b)

“Then Christ will make his home in your hearts as you trust in him. Your roots will grow down into God’s love and keep you strong.” (Ephesians 3:17)

Jubilee

As I consider the soil under my feet and the diversity necessary to grow a sustainable and thriving Eden, I can't help but think about that ancient Hebrew law that required land to be Sabbathed every seven years. It would rest from production and be replenished so that it could flourish once again. What if we followed in suite, Sabbathing every seventh year? Would society fall apart? What about our lives? And would that be such a bad thing? In some ways, we too are like soil.

“And you are God’s field.” (1 Corinthians 3:9b)

In addition to these land-Sabbaths every seven years, every fifty years was the Year of Jubilee.2 In Levitical law, on this year, slaves were freed and the resting land was required to be sold back to the families who originally owned it. The Year of Jubilee was radical! It played a major role in economic and social justice, ensuring that each generation had a way to restart, to come home. This created some limits to how rich and powerful people could become off the land, while providing restoration for those pushed out.

Justice isn't just for law and society, but it goes deep into the earth, rooting into the same soil I dig my fingers into.

And as I do, I pray and plead for Jubilee to come again, to be birthed into my life and into our world. All while I try to draw contentment from the daily rhythms of planting, plowing, planting, weeding, and patiently waiting for a harvest I cannot produce to be grown, like miracles and magic from the life-force that animates each breath.

“But it was God who made it grow.” (1 Corinthians 3:6b)

Land

Like the paintings of the ocean on my wall, Jubilee reflect the nature of God’s Kingdom. And yet, land ownership is actually one of the most hotly debated items in the arena of politics, nationalism, and activism today. I was so surprised Lore gently went there, to question the norms of each approach. And I was so grateful she did, for she put words thoughts I’ve never dared to form.

I wonder if the reason we bicker about land isn't as much because of the issues we bicker about, but because we don't spend enough time wondering if space can even belong to someone. Or does land simply reflect the image of God, who gives of himself by choice as our Beloved, and yet is still as mysterious and ungraspable as the wind?

Even as we continue to watch the trauma and horror in the Middle East extend, I wonder what a year of Jubilee looks like for a people who must learn to share. This is another sorrow that weighs heavily on me. It is the way of war, and it is anything but new. I dared to write about Israel/Palestine last fall here. I am glad I did. But by “new” I am not just referring to this new spike in an ancient conflict in the Middle East, but through every conflict recorded and unrecorded in history.

The talking stick

We had a woman over for dinner recently. She talked a lot. I can talk a lot, too, but she far exceeded my norm. It didn’t bother me much—this night was for her.

When I’m the quiet one with a near-stranger for hours on end, it causes me to reflect on how others feel around me. Do I frequently monopolize a conversation? Is it showing mutual interest? Am I caring through my questions and body language? (I actually think about this type of stuff a lot, as evidenced here.)

And each relationship is different—often through unspoken rules for who has the floor. It can be disappointing when our expectations aren’t meet.

While finishing up the revisions on Justice-Minded Kids, I noticed that one of the lessons I wrote for it long ago requires a "talking stick," or a “speaker staff,” an Indigenous communication tool. The origins for this tradition are tied to a variety of tribes, and it was used democratically. In one story,3 using a talking stick was how warring tribes resolved their land disputes, for communication and all it entails is a powerful tool of justice.

I’ve used talking stick democratically myself, mostly to teach my kids etiquette or to address challenging topics within my family. Communication is its own type of land that must be shared.

Defining the understory

Did you know the understory is a name for everything that happens under the canopy of the trees? It is the moss and the mold, the worms and decomposition, and the birds and their seeds.

After we finally made it to the forest that day, I was determined to observe the understory of the eucalyptus-lined trail. I was sure it would be contemplative, as I moved along, pausing with my toddler to observe a bug or something else on the forest floor.

Instead of a pleasant walk between the enshrouding trees, my toddler fully embraced his newly christened terrible two's. We didn't get very far. And where we did walk, much of it was accompanied by his recklessness, defiantly disobeying me as he'd attempt to throw massive rocks over his head, or nearly tumbling down the embankment to the iron-tinged-orange stagnant water in the crevice below. He was outraged and in tears most of the time; I let him throw himself in the dirt in protest (or exhaustion) more than once.

I finally called it, carrying him over my shoulder so we could go home and take a nap. I was disappointed that I wasn't able to hike, despite my best intentions. However, I also understood. I've had my own tantrum or twenty along life's paths.

I began to wonder if this was my own study of nature; a unique contemplation of the understory.

I am here

Lore Wilbert goes back over and again to the phrase, "ecce adsum." Or for us who don't speak Latin, "I am here.” And I am here, just as baby Kai is. And God is. As as are the trees around us.

And maybe that is how I found myself engaging in this book, breathing in and out the prayers,

"I am here.

You are here with me.

I am dying.

And I am dying with you.

I am rising.

And I am rising with you."

In the moss, mud, and soil we find death, life, and all the transitions in-between. We grieve, mourn, and find acceptance. But in the understory there is also curiosity, and rebirth. The understory is where I am and that is here.

Re-loving books

A metaphorical talking stick was passed to me in the conversation with our dinner guest when she asked me how I began to love reading books. She hasn't loved reading since before college, and that was over two decades ago. I understood where she was coming from.

When I studied cultural anthropology and global issues, I read a lot of depressing texts. One week it would be a heart-breaking memoir about poverty, the next a journalistic unraveling of politics and immigration, and following that, an ethnography of the West clashing with local tribes, debating the merits of globalism. I spent hours reading "We Wish to Inform You That Tomorrow We Will be Killed With Our Families" on the Rwandan genocide less than fifteen years after it happened, then heading to class to discuss for hours the genocide that was happening in Sudan at the time. Unfortunately, the later is an essential contributing factor to the scene we’re seeing playing out in Sudan now, with millions on the verge of starvation because of complex dynamics of "neo-capitalism." And I don’t want to read a book about it.

As you can imagine, by the time I finished college with a baby on my breast, and a toddler at my feet, I was done with books. I didn't regret learning about injustices and land-clashes, but I was tired.

However, at the same time, a close friend of mine started a successful young adult fiction book vlog. She’d collect boxes of ARCs and finally she convinced me to pick one up. I was enthralled. Reading fiction gave me an escape from my daily lament of real world injustices.

And so, although I might write about justice myself, I’m buoyed by stories. Despite the heartbreak, the suffering, and poignant challenges that build the plot, there is always hope. At best, there is a happy ending. At minimum, a resolution of the tension.

I am wired to long for this. And as our human story isn't finished, yet, I continue to hope for restoration. I manage to live each day because I believe in a Someday. Or maybe it is Somewhere, a land that isn’t fought over, where the lion will lay with the lamb, and tears will give way for joy. I believe in rebirth; I believe in wholeness.

And even as I live in the understory now, I hope in the more to come.

As Lore points to her favorite poet:

"The coming of the Kingdom is creation coming to be what it was meant to be."

-Madeleine L'Engle

The right words

This week, I had to say goodbye to my therapist of two years. She has been with me through the worst season of my life. It was heartbreaking and hard. In our last appointment, I avoided the inevitable end to our relationship, talking without a talking stick about The Understory.

I wasn't sure how to define this book, let alone describe it. Was it a compilation of essays? Or was it more of a meditation, a contemplative mindful and meandering set of metaphors? What do you call a book that helps you become present, to notice the ground beneath your toes?

I felt like I followed Henry David Thoreau to Walden Pond in the forest only to discover that both Lore and I are actually Thoreau, yet a Thoreau still clinging to a God-centered worldview, despite the horrific experiences we've had. We see nature as a beautiful way to process pain.

As I spoke with my therapist, I kept coming back to questions that Lore put words to and experiences both the author and I shared. I found myself tying the author's ideas back to situations in my life since "everything fell apart," helping me give them meaning. I expressed that the author must have been in my head when she wrote it, reflecting my own thoughts, doubts, and curiosities.

My therapist finally stopped me, reclaiming the talking stick and saving me from my frustrated attempts to describe The Understory. "It sounds to me you feel this book is a friend. It is obvious that you feel understood. It is a reminder that you aren't alone."

Oooh, yeah. That’s exactly it! (She also told me that despite my poor attempts at describing this book, I was doing a pretty good job selling her on it.) Only when I eventually received my hard copy did I notice author

’s endorsement on the front cover, "This book is one I didn't know I was waiting for." Neither did I, Emily, neither did I.So if you're also in a strange liminal space—having changed, become, and are still pursuing wholeness—The Understory might also be for you.

It is fascinating how God can connect us with the right words at the right time to carry us through a season. This is especially meaningful for me to hold onto as I say goodbye to my therapist. I keep going. Even if it is just to sift fertilizer through the soil under my loquat tree.

I hope that today you also find a tree. Linger under it a little while. Run your fingers through the earth beneath it. Marvel at what you see there, tracing your connections to the ground. Inhale the prayer, "I am here…" and exhale, "…and you are here with me." As part of creation, you are nature, too. You belong to the story. Now live, breathe, and have your being.

If this post was helpful, please tap the heart 🖤 icon and leave a comment. Your engagement encourages me greatly. And when you engage here and/or share this, it helps these words reach others waiting for them. Thank you.

You can find past posts visiting authenticallyelisa.substack.com

Follow me on Instagram here @AuthenticallyElisa

On Average Advocate this week: When You Don’t Know What To Do…

Matthew 21:18-22 and Mark 11:12-25